For a while now, I have been feeling unmoored. And because I am the kind of anxious person to capture this feeling and disassemble and splice it I can pinpoint its origins to a few things.

The first is a gradual dislocation between the city and self. For years, I have been feeling at odds with Colombo as it morphs and recasts itself. Even after three decades of living in Colombo, I go to events and have an endless feeling of being on the outside looking in and uncertain of where I fit. Of being on the fringe of humming friend circles but never immersed. With close friends migrating from Sri Lanka in recent years, it soon became apparent that my experience of the city was largely through the people I love. Having a partner in another country a few thousand kilometres away and with both of us mired in the paperwork and uncertainties that accompany third-world passports and first-world borders has also deepened this dislocation, leaving me in a liminal state.

Another is the accumulation of a series of rejections. Rejection and I, we are old acquaintances. I have been on LinkedIn and the buoyant side of Instagram long enough to realise that rejection is: a) redirection b) God’s plan c) a blessing in disguise d) an inevitable fact of life e) an opportunity for growth. I am trying to grow the thick skin required to plough through the many rejections that await me but the last writing-related rejection which came in January — a South Asian writing mentorship program that I had applied to thrice before and was fervently hoping would shape my writing this year — punctured me in a way I did not anticipate. Perhaps it was because the news came when I was also job hunting and dealing with multiple work-related rejections and ghosting. Perhaps it was exacerbated when certain plans for the year cracked wide open, upending my annual colour-coordinated Excel sheet. Perhaps in my head I had given this fellowship too much importance and unwisely hitched my self-worth to it, thinking that the fourth time would be the charm. Added to all this, was a sense of helplessness and frustration writ large watching multiple events around the world and in this country play out. While I might have dealt with each thing on its own, this convergence of multiple dislocations has unseated me over the past months.

//

When I am feeling adrift in Colombo, there is a place I visit to feel grounded. It is located in a fluorescent light-lit food court in the belly of an aged, 33-year-old shopping complex in Bambalapitiya. Tucked away in the food court of an old mall in Colombo named Majestic City is a kiosk named Peppers Pizza. Peppers Pizza’s only outlet in the country has been situated for more than thirty years in this food court. For many who grew up in nineties Colombo, a slice of Peppers Pizza is synonymous with the building it is housed in and is an edible memory of a past version of the city. This city has changed, governments have changed and toppled, I have changed and also occasionally toppled, but the pizza at Peppers Pizza has remained a constant. For as long as I can remember, it has been the same moustached man behind the counter who handles orders.

I first began examining my relationship with Peppers — and by extension, MC — in 2018 when Roads & Kingdoms, a travel magazine founded by Anthony Bourdain, reached out to commission a few articles for their upcoming Colombo city guide. What appealed about the commission was R&K's approach to travel, which ran counterpoint to the breathless, PR-adjacent, ahistorical travel writing that had begun to flourish on the internet. At the time, I had just returned to Sri Lanka after doing my master’s thanks to a scholarship. I left Colombo, burnt out after a prolonged period of freelancing and personal upheaval, ready for a change of scene and hungry and eager to learn again. I returned rejuvenated, but also feeling like the year had slipped past me. I returned to find that Colombo had changed and I had changed. For a few months, we began getting to know each other again, trying to figure out what our renewed relationship would look like. This writing commission came at an ideal time.

R&K had a series called shitty but we love it and one of the pieces I was working on was an essay for this. It was then that I realised that when I was away from Colombo for a long time and needed a place to find my footing, I returned to Majestic City and so I opted to write about it for this series, unpacking why this was my urban lodestone.

//

Apart from Peppers Pizza, my earliest memories of MC is of the children’s play area in the basement. My first initiation to arcade games, air hockey and bowling was in this play area. There was a children’s toy shop near the play area and I often clamour to go there, marvelling at the toys, looking at barbies with a hushed deference as we could not afford them back then. When cousins from out of Colombo visited, we would take them to MC and the play area. Tired after playing, we’d bury our faces into too-sweet candy floss, the pink crystalized sugar crusting our cheeks. While speaking to friends about MC, they recalled family excursions during Christmas to meet “Santa”, often an underpaid young man with whiteface and an unconvincing belly consisting of a pillow that would migrate in various directions under his suit.

As a school child, MC was the ideal place to make the most of limited pocket money. You’d be able to buy the latest Now That’s What I Call Music! CD and luxuriously indulge in a soft-serve ice cream at the KFC in MC (the country’s first KFC outlet). I vaguely remember always going to MC chaperoned when younger or with a larger group, never alone. The gaggles of boys who roamed the complex were disparagingly referred to as MC dudes and girls were fearful of being seen loitering in MC, thanks to the social anxiety drummed into us.

One of the earliest shopping malls in the city, the grandiosely-named Majestic City was constructed at a time when Sri Lanka was in the midst of a brutal civil war. While the conflict was fought in the north and northeast of the island, as the business capital of the country, the threat of attacks often hovered over Colombo. Completed in 1991 and subsequently expanded on in tranches, the shopping complex was built on the former site of Majestic Cinema owned by Ceylon Theatres, an adjacent company of CT Land Development, which owns the shopping complex. Like many Sri Lankan corporate narratives, MC's origins is mythologized in corporatespeak recounting how despite purported scepticism about the project, Albert A. Page had a vision for Colombo and began constructing Majestic City. A 1987/88 annual report outlining the building plans for MC contains the cosmopolitan aspirations of the shopping mall in buoyant corporate prose: central air conditioning! escalators and elevators! a luxury cinema! offices! apartments! continental and fast food! convenience under one roof!

Majestic City – both in 2018 when I was first excavating my fascination with it, and perhaps even more now – occupies a halfway-house status in Colombo’s topography, toggling between a version of Colombo past and the aspirational Colombo of the future, chafing uncomfortably with Colombo’s new urban recasting. With its fluorescent lighting, sparse interiors and matte chocolate and ochre palette, the shopping complex lacks the history or “colonial charm” (a travel guide’s words, not mine) of most city landmarks that tourists seek out. The mall also doesn’t fit into the sleek, Instagrammable aesthetic that newer additions to the city trip over to emulate. For many, MC’s gild has diminished in comparison to new malls which have opened in Colombo. When speaking to store owners in MC in 2018, they lamented the lack of footfall, plummeting sales and insufficient parking facilities which they claimed was a deterrent for customers. New shops had transitory lifespans – opening and closing within a few months.

//

To live in Colombo and its suburbs is to be reminded of urban impermanence and the frailty of cities. The family-run restaurant where you polished off a rice and curry last year could be a garage the next year. The roads you grew up with are renamed with astonishing rapidity. The city’s preferred method of memorialising people is to honour them with a road; there are many old potholed roads with new names.

Malls are part of urban infrastructure designed to increase consumption and MC is no different. The key to enjoying Majestic City in its current iteration is to stop comparing it to a contemporary mall. What sets MC apart is its comparative affordability and mishmash of stores. When the brands you adorn and are loyal to are perceived as markers of social mobility and aspirational lifestyle, there is perhaps a loss of the realm of possibilities beyond the branded, hyper-consumerism that marketers and social media envision for us. A lot of the shops in Majestic City are shops which are slowly receding from Colombo’s built landscape – small businesses battered by the triple-prong of the Easter Attacks, COVID and economic crisis, unable to compete with companies backed by larger corporate funding or unable to contend with escalating city rent and overheads. Some relocate to the suburbs, many close permanently.

When I kept returning to Majestic City in 2018, what struck me most was how there were items you’d be hard-pressed to find anywhere else under one roof. An assortment of objects which flatly flout the polished conventions of contemporary malls: the entire series of Dawson’s Creek (definitely pirated, as grey market shops abound in the area), a bust of Shahrukh Khan and Preity Zinta, an impressive range of Che Guevara, Tupac and Bob Marley t-shirts, a painting of Jesus Christ made from coloured sand, bodybuilding supplements, hats, harem pants, bottled pol sambol and batik clothing modelled by a cutout of a fresh-faced Shihan Mihiranga, once a national heartthrob thanks to the first season of Sirasa Superstar, a local take on American Idol. If you were to take a stroll through its floors back then, you were likely to come across camping gear, winter clothing, saris, branded and unbranded perfumes, spices, musical instruments, sports equipment, embroidered children’s clothing, jewellery, evening gowns, toiletries, ceramics, makeup and pickles. A few years ago, a friend who was visiting from India broke her travel bag. We went to a store that sold branded luggage, and her face blanched and she confessed they were out of her budget. We dropped in at MC and within a few minutes, found a suitable replacement.

“Not everyone can afford the high-end, branded items being sold in the new malls. The thing with MC is that there’s something for everyone,” said a shopkeeper who ran a jewellery store inside the shopping centre, when I spoke to him in 2018. On a whim, I went looking for his jewellery shop after one of the COVID lockdowns to see how he was faring and encountered an empty, abandoned showroom where his shop had been.

//

The problem with failure and rejection is that when it coagulates and hardens into the crevices of your life, it is hard to scrape off. Before I knew it, shame walked into the pity party and refused to leave. A few years ago, I cleaved my professional work practice and creative practice into two disparate parts. I’d been working as a freelance writer for a decade but decided to step away from writing professionally for ‘work’, pivoting more into communications. I hoped this decision would provide the financial stability and space to focus on and be bolder with my creative practice but now a few years down the line, I am still nowhere close to the writing milestones I had envisioned for myself.

This year, all the spectres of my past failures are haunting me, taking residence in my head, mocking me for all the things I did and did not do. I have tried exorcising these spectres. Talking to them. Airing them out in the sun. Making friends with them. Praying them away, forehead pressed on a velvet prayer mat while in sujood. I walked into a house which had a shop on the ground floor where I saw a girl angry-sad-dry-heave-sobbing as though someone dear to her had taken her fiercely guarded secret and announced it to the world, and lay on a bed on the upper floor with my eyes wide open while a lady hovered her hands over my body and told me my heart was filled with grief and charged me Rs. 5,000 for this insight. In the absence of a cohesive creative practice, I pour myself into a physical practice, walking in the evenings amidst traffic fumes and lengthening my body into deep stretches. Every week I relished contorting and pushing my body, which has thickened considerably in the past year, to new limits. On my walks, I pass by a man in his seventies who has inhabited a bus stand. Gaunt, unshaven and grey, he sleeps on a mat and a single pillow, sometimes drying his clothes on the roof of the bus halt. Once during the day, I passed him as he sat on the opposite side of the road against a wall with his face turned towards the sky as a road sweeper in a neon orange vest trimmed his beard with a pair of scissors. Yesterday, I walked past where the bus halt usually stood and there was nothing there — there was no trace of the man or his belongings, and even the bus stand was dismantled. I paused in the location wondering if I had dreamed him. All that was left of both beggar and bus stand were a few ridges where the paving had been dislodged and marks on the pavement.

I saved opportunities but did not apply and sat in front of half-finished drafts day after day steeping in self-doubt and wondering why I persisted in writing. I felt further and further estranged from this city — Colombo loves a polished success story, there is little room for misfits and stragglers — and from my writing practice, and began to recede further into work, job hunting, anything else. Margaret Atwood wrote that a word after a word after a word is power but when the words don't come and when it is all you know how to do, how do you reclaim your power?

Failure and rejection are constant companions in the writing journey. To commit to writing and be ill-equipped to deal with failure is like walking into a storm without an umbrella and then being outraged that you got wet. In his book Writing and Failure, Stephen Marche lays out various anecdotes and aphorisms of largely white, male writers to drive home precisely this point. In one anecdote, a writer is lunching with Philip Roth and asks, “Is it ever easier? Do you ever grow a thicker skin?” “Your skin just grows thinner and thinner. In the end they can hold you up to the light and see right through you,” answers Roth. “Failure is the body of the writer’s life. Success is only ever an attire. A paradox defines this business. The public only ever sees writers in their victories but their real lives are mostly in defeat,” writes Marche comfortingly.

The past year has been a process of finding new ways back to my writing practice, to give myself grace, and find pleasure in it instead of giving into self-flagellation and what Natalie Goldberg refers to as ‘critical discursive thoughts’ (“The continuation of writing through all your discursive thoughts is the practice.”)

Simultaneously, it has also been a process of trying to recalibrate my relationship with this city and returning to spaces that rejuvenate me, carving community in a city that is not designed to nourish community but to heighten consumption. During covid and lockdowns, the beach was a space I frequented and felt comforted by — not the beach along Bambalapitiya/Wellawatte, I haven't visited or felt the desire to visit this stretch after I came across a man masturbating in the bushes 15 years ago. On a particularly stifling weekend, I coaxed my family out of their Sunday nap stupor, persuading them to come with me to the beach. We soon arrived at a crowded beach littered with garbage a few minutes later, filled with people also trying to stave off the heat. I sat with my feet buried in the sand, reading a book of poetry while my 88-year-old grandmother hitched her kaftan up to the knees of her varicose veined legs and watched the sun set.

On some days, this process of dual calibration means sitting with a series of questions. Why do I write? What do I have to say? Do I have the tenacity to continue writing even if I do not attain conventional markers of success? Where in this city did I last feel energised and excited? Where in this city do I go to feel comforted?

On some days, engaging in this process means reading and inhaling books on craft or revisiting old re-reads. Seeking out new rituals and new ways of seeing and being instead of giving into restlessness and despair. Or venturing out more into the city, moving with curiosity, allowing it to surprise you. Making time for the people you love. On some days, this can mean returning to the food court of an old mall, with your notes spread on a formica table while eating pizza and writing on a phone. There are so many paths on this journey. Perhaps the key is to acknowledge your failures and keep moving.

//

These days, Majestic City has a desolate air to it. Several larger businesses have withdrawn from the premises, shifting to newer malls. “Same as it was 10 years ago,” grumbles tna2002, a reviewer on a travel site. “Our favorite mall in childhood. Lot of memories. Nothing has been changed. No renovation. Same old shops, same food court.” The crowds at MC have thinned. That is not to say that it is empty – with a train station hugging it from behind and a bus halt in front, the shopping centre is easily accessible through public transport and still affordable to many, unlike newer urban spaces in Colombo. The food court is plastered with ads featuring brands of the mall’s parent company with fair-skinned models consuming the company’s food products in various stages of orgasmic ecstasy, and enjoys a healthy footfall thanks to affordable food options.

The ecosystem around the mall has changed and keeps changing. Shops open and shrivel up on Station Road within a few years. Earlier, Eagle used to be a favourite for pirated DVDs. When I began working soon after I finished school, I would keep aside money from my sparse salary to buy pirated movies from Eagle – never mind, the fact that I did not watch most of the movies I bought, just having the stacked DVD boxes filled with the promise of movies yet to be watched gave me a misplaced feeling of wealth. A popular horologist opposite the mall closed down seven years ago. Colombo's development is often built on top of layers of urban violence and displacement and I often wonder what displacement took place when MC was built.

On the upper floors of MC, there are numerous showrooms which are vacant and the second floor looks especially forlorn. Some empty shops give the impression of tenants leaving in a hurry: graveyards of headless mannequin torsos strewn on the floor, chairs upturned, small hills of dust swept into a corner but not cleared, christmas decor still up.

The R&K pieces were never published: the constitutional coup in Sri Lanka happened, then the Easter Attacks happened, then covid happened, then the economic crisis happened. Somewhere between all of this, R&K pivoted towards being more of a travel experiential company instead of a travel publication. I returned to freelancing recently and suddenly remembered that I never sent my invoice to them for the work I did and got in touch with them recently and they kindly (and swiftly) responded with the payment.

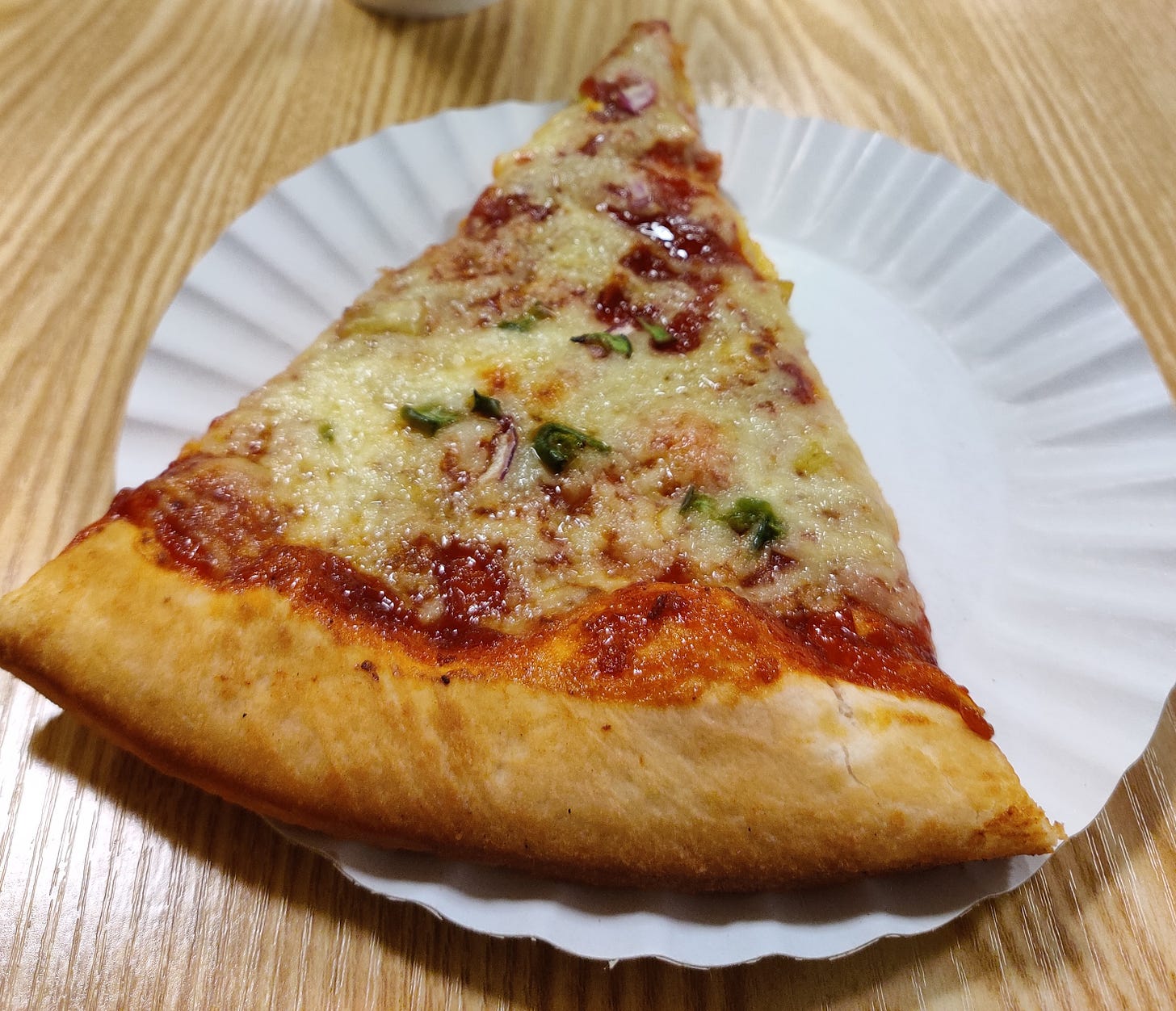

A few weeks ago, I was in between meetings and needed a place to recharge. Because I was in the area, I inevitably found my way inside MC, went to the food court and made my customary pizza purchase. For as long as I can remember, Peppers has had a window display featuring dubious, congealed versions of the dishes they make. I have never ventured to eat anything else at Peppers for fear that I would not enjoy it and that it would unravel all prior experiences at Peppers. If you’re in the habit of documenting your food, your phone will remain firmly in your pocket. It is a piece of pizza that will never make its way to glossy, travel listicles about Colombo. Sold by the slice (Rs. 200 in 2018, Rs. 450 now), the pizza is one of the kiosk’s fastest-moving food items.

I survey the slice with the same appraising gaze some people survey a house they intend to buy. There are no peppers in Peppers Pizza, the sauce has a pleasant sweetness to offset the tartness of tomato, pieces of onion liberally punctuate a thin layer of cheese. The meat-to-sauce ratio has diminished over the years – culinary collateral damage of an economic crisis. I bite into it and close my eyes. Tastes the same every time.

A very touching piece!

These Saturdays are always worth waiting a while for. Thanks for sharing.