“At the trial of God, we will ask: why did you allow all this?

And the answer will be an echo: why did you allow all this?”

— Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic

Ta-Nehisi Coates

1/

Once as we kept wait outside an ICU, my sister and I made a pact. If either of us were ever on life support for a prolonged period, please pull the plug we decided. Dying, we decided – as though we have control over these things – should not be a painful process. Dying should be kind to the living.

I dress rehearse death often. It’s an accidental aftershock after the unfolding of a worst-case scenario with a loved one a few years ago — the kind of thing you always hope will never happen. I think about funeral costs. Parking arrangements. Refreshments for visitors. Cleaning. The paperwork to make a death official. How to disentangle a body from everyday effects that tether it to daily life: bank and utility accounts, real estate, books, clothing, electronic devices, phone numbers, passwords.

It's a morbid preoccupation. I don't know why I do this. And because this pandemic has bought living and dying to the front of my mind, I also catch myself wondering how I will die, how old I will be, who I want around me and what a well-lived life looks like.

2/

My faith indents my daily rhythms, my identity. It is a part of who I am.

I pray every day. When I am relieved or grateful, ‘Alhamdulillah’ is an instinctive exclamation. The word ‘Insha Allah’ – if God wills – is an acknowledgement that life is uncertain. It's also become a playful word to commit to something without really committing to it. There are memes. Before I make any major decisions, I intuitively turn to Isthikhara, a prayer that provides guidance. Not because I am expecting divine intervention but because for a few minutes it helps me to slow down and reflect. And maybe that is what prayer and religion are supposed to do – help you quieten, go inward and take stock. These things can also be done through other means. Whatever works for each person.

People's inner beliefs seep into their outer lives in similar ways. The lady who plucks flowers from other people’s gardens for offerings, collecting it in a polythene bag dangling from her wrist. An incense stick perfuming a shop in the morning. A wizened uncle who leaves out food and water for stray dogs and cats every day. Sunday cadences modulated around the timing of mass. Same same but different.

Islam was a part of my childhood. As I became older I chose to retain this part of my identity. Stuart Hall writes of how identity isn’t a set of fixed attributes – “a singular, complete, finished state of being” – that can be transplanted onto a person (Ctrl +V. Done). “Identity is always a never-completed process of becoming,” he notes. He writes specifically about diaspora identity but this is pliable enough to be extended beyond it. You are not the person that you were a decade ago. Isn't it normal then that your identities also transform?

I interrogate what ‘Muslimness’ means to me. I tussle with some of the cultural and patriarchal practices calcified within the faith. We grew up reading the Qur'an in Arabic but without understanding what it meant. When I was older, I began reading multiple translations. Each translation feels like gradations of one colour — a word, different sentence constructions can alter meaning so implicitly. And this interrogation only intensified. The problem with religious scripture is that there is a lot of room for inference. There are some pitfalls when men mediate God for other men.

There is also a thick sludge of global Islamophobia which has settled over mainstream discourse muddying a lot of Islamic history and culture. Sometimes it’s the visible, easily recognizable kind. At times it’s seemingly innocuous things — discovering that what you conventionally know of Rumi’s poetry which proliferates the internet are translations done by a white man scammer who did not read or write Persian and stripped the poems of the spirituality which suffused it (…to call these translations feels like a generous leap in imagination). Being Muslim means a lifelong process of constant re-education and reconfiguring what you think you know.

My personal guiding light is the spirituality embedded within — the spirituality I feel that is sometimes lost in the rigours of organized religion. The God I believe in is forgiving. The religion I subscribe to prioritizes kindness and empathy. It leaves room for the fluctuations of faith and doubt, for all the messiness and imperfections of being human. When I was younger, religion was tied up with morality and goodness but as you get older you realize these aren't always intertwined.

The way religion has shaped my life will not be the same for someone else. I am sure my halal:haram ratios might look askew to someone looking outside in. Perhaps it is important for Muslims to hold space for differences instead of casting judgement.

To be Muslim in Sri Lanka offers added complexity. The Muslim community is made up of multiple denominations within and practices differ. There is beauty in diversity, there is also disarray. The (male) Muslim leaders who are appointed as stewards grapple with changes within and without. A reluctance to self-reflect and a sense of preservation, which arose because of events in recent years, has resulted in tunnel vision. I look at certain things embedded within the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) and wonder how it has endured for so long without reform and why men cling to anachronistic man-made laws like it is a God-given right.

For some of us, being Muslim means to constantly assert our agency within our own community, to remind that Muslims aren't a monolith. That Muslim women’s bodies aren’t men’s battlegrounds and that Muslim women have agency. To rewrite new narratives within the faith but outside conventional tropes.

Some are deemed too Muslim and are forced to edit our identity to accommodate other people’s comfort levels. Some of us aren't considered Muslim enough, judged by a lack of external religious markers. Navigating these piety Olympics while figuring out your own faith is a part of being Muslim. I can speak only for myself here. I am just one person trying.

To live in Sri Lanka as a Muslim is to frequently find yourself justifying your existence as a Sri Lankan. That you belong here. This is the only home you know. For Muslims who have religious markers – a hijab, a beard, a cap – there is added judgement and sometimes, overt discrimination. With these markers come a set of ascribed perceptions. You are pre-judged before you say a word. You're judged within the community, you're judged from outside. Shukra Munawwar, a 17-year-old student, was hailed with enthusiasm for winning Sirasa TV’s Lakshapathi quiz programme recently and for her eloquence and knowledge of Sri Lanka. And rightly so — my heart was full seeing her. It was refreshing to see a young Muslim woman on TV outside the Muslim narratives that dominate Sri Lankan media. People remain flabbergasted by her intelligence and humour because she chafes against the Muslim stereotypes that are now fixed in the public imagination.

A lot changed after 2013 and after the Aluthgama riots. Or maybe the riots brought to surface a simmering energy which was latent for a while. I don’t know any more if these things are linear or what is organic and what are political machinations.

When people speak about the Easter Attacks, there’s a tendency to theorize it in a vacuum. As though it existed outside Sri Lanka’s post-war context. As though it occurred outside the ethnic bigotry that has rotted the country’s core for years, fattened voter banks, lined pockets and is not tackled with. As though the coup in November 2018 was only a soap opera political fable about a defeated man so desperate for power, he crawled back to the Brutus who betrayed him. Or relegating the coup to men chucking constitutions, chili powder and chairs at one another and not as political infighting that had dire impacts on the machinery of a country and left a trail of bodies in its wake months later. As though an anti-Halal campaign, anti-Muslim riots, rumours of sterilization, the burning of Muslim-owned homes and businesses compounded by a lack of accountability and state complicity would not have ripple effects – many have pointed out that the mastermind of the attack strategically moved to areas which experienced anti-Muslim violence.

What I mourn is the lack of mourning that was afforded to those affected by the attacks. Before we could grieve and heal and demand accountability from those who had known for weeks about the impending attacks and still allowed it to unfurl, we swing into a surging anger and anti-Muslim hate that is stoked regularly.

Dr Shafi’s story is a textbook study of how to destroy a person without exerting physical harm. A national newspaper ran an unsubstantiated article tacked to a spider-web strong rumour about a doctor in Kurunegala who purportedly sterilized 4,000 women without their consent. The GMOA and many medical professionals around the country remained silent in the face of these allegations: that a Senior House Officer (SHO) who works under the supervision of a consultant and is accompanied by a team of at least 6 could secretly sterilize thousands of women without anyone noticing and work to single-handedly reduce Sinhala-Buddhist birth-rates. The media witch hunt whipped around Dr Shafi dominated the news for months. His photograph, his personal details were in every newspaper. His wife and children were threatened. He was arrested and witnesses were produced. It was discovered later that his colleagues in the Kurunegala hospital and law enforcement authorities had concealed and fabricated evidence and altered judicial records. The case against him fell through months later. Every now and then news reports surface about some of the women who claimed to be sterilized by Dr Shafi giving birth to babies. His career now remains ruined. I wonder where he is now.

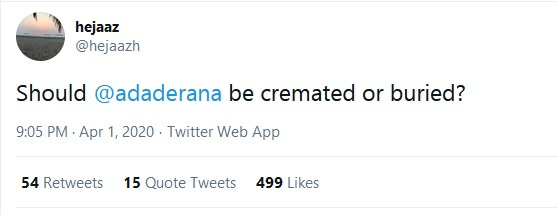

Hejaaz Hizbullah, a fairly well-connected Muslim lawyer and a critic of the current regime, was arrested in April 2020 under suspicion of being linked to the Easter bombings, just around the first year commemoration of the attacks. For 9 months, he has been held without charges, without bail, was repeatedly postponed legal assistance, has contracted COVID-19 and missed the birth of his baby daughter in November 2020.

I first heard of Ahnaf’s case only in December 2020. He was arrested in March 2020, lacks connections and didn't get much media publicity. He had no legal representation until recently. Ahnaf Jazeem is a 25-year-old poet and teacher and one of so many arrested under the PTA. His poetry was political. A poem critical of the Islamic State had a poem of an IS fighter in a uniform and because the CID officers didn’t know Tamil and couldn’t read his poetry, they arrested him. A court had child psychiatrists examine word-to-word translations of his poems. These experts in child psychiatry concluded the poems could be harmful to minors.

Just for a moment, I invite you to sit with the absurdity of asking medical professionals to assess abstract poetry. Perhaps poets will soon be performing heart surgery and administering medicine for diabetes in this inverted world.

This is a précis of prejudice from a longer list. It is also a new page in an old Sri Lankan playbook against minorities.

I think of this line from an essay by V V Ganeshananthan over and over again. It has come to me unprompted during oddly unexpected moments so many times last year: “…because in this country of grief, the best kind of shelter is to be understood, to have someone stop next to me and without asking anything, put their umbrella over us both, between us and the rain.”

Perhaps I am laying out all this in the hope that I will be understood.

3/

On Saturday, 28 March 2020, Sri Lanka recorded its first Coronavirus death. A 65-year-old man with a history of diabetes.

There was an element of spectacle and state performance in electronic media coverage to emphasize how the public is being protected by the military which is leading the country's pandemic response. The entire cremation was televised.

One family member was allowed to be present and they showed the bundling of a plastic-wrapped body on a stretcher, its transportation in an ambulance and its cremation. The camera zoomed into the PPE worn by a staff member and there was a shot of a military official giving instructions on how to disinfect the crematorium after the incineration. I wondered how the family felt about a private moment held up for public consumption.

Our family watched the news, silent. We had been in curfew for a few weeks and the virus was still new, the numbers were few. Something shifted that day. The first death felt personal. I closed my eyes and thought of the life that was lost, wondering what the next months would bring.

4/

This island is built on bodies. It has a heavy history of stripping dignity from the dead.

A 26-year-long war is bookended by bodies and a refusal to reflect on the violence which birthed these bodies. Spilling out of this are murders, pogroms, denials of death, rumours of the dead. Years ago, a journalist’s car was shot at while he was driving to work one day. His head and heart were then stabbed with an instrument similar to cattle prods. What does that say about a country?

What does it say about the psyche of a country which has so many disappearing bodies and so much of paralyzed grief that there is a government department called the Office on Missing Persons? Every now and then a social media post surfaces of frail mothers holding up photographs of their loved, protesting, holding vigils, searching for answers and for corporal bodies to attach to waning memories. Unfailingly, you will also find comments under these posts calling these a western conspiracy to derail Sri Lanka. A few weeks ago images began pouring in of a public war memorial in Jaffna University bulldozed by the authorities late at night. One of the artists involved in the design of the memorial lost his father in the final stages of the war. There are now promises to rebuild the memorial but its destruction was Big Bully Energy: what you build, we can break. We want you to remember this.

The 2004 Tsunami killed over 35,000 people in Sri Lanka. More bodies. Thousands of bodies were dumped abruptly in mass graves without identification, barring local forensic pathologists from collecting information, "leaving enormous problems for the living and the courts in the future". Recently, I read of a family still looking for their missing daughter, holding onto hope that she is still alive 16 years later. What loomed large after the Tsunami was the siphoning of relief funds meant for victims and donated by the public – people building bloated fortunes from carcasses.

When I thought our capacity to grieve had been overextended, when I thought this island couldn’t bear the weight of more bodies, we saw violence in 2019 which is going to have and is already having insurmountable effects.

When I think of the Easter Attacks, I think of those in power who knew about the attacks and the perpetrators well before and decided not to do anything. The government, the intelligence and many VIPs were made aware of specific details about the who/where/how/when’s of the attack and chose not to stop them. So much has happened since that these details are now absent in the retellings of the attacks today and no one in power has been held accountable.

I think of a video of a defence secretary on the defensive. There is a clip of him speaking to the media just before he is driven away in his car; no remorse, grief or humanity in his responses. This stance mirrored many of those in charge. In one press conference, they attempt humour. The 269 bodies that were lost meant nothing to them.

“Why this string of failures and demonstration of incompetence by the political establishment is not at the centre of narratives being produced – rather than the failures within the Muslim community – speaks to the heart of the enabling conditions for such attacks in Sri Lanka. It also speaks to the casual and pervasive racism that is institutionalised within the Sri Lankan polity. Rather than holding accountable those responsible for the wellbeing and security of the population, and examining how we allow political survival and self-interest to drive the priorities of Sri Lanka’s political leaders, we turn instead to the much easier target of blaming yet another minority community for just not trying hard enough to be good enough second-class citizens,” writes Harini Amarasuriya.

There was a news clip showing a macabre, public prize giving-like event doling out bereavement money for those who were injured or had lost loved ones in the attacks. The VIP who was supposed to distribute the money was late to arrive. Waves of discontent began rippling in a room thick with grief and pain.

“I don't want this money," one man angrily told the TV camera while exiting the hall, tired of waiting for the VIP.

He points to his maimed leg. “I’m injured. I lost my family. They don’t protect us and now they keep us waiting to receive the money due to us? Let them keep it.”

5/

Fahim (28) and Shafnaz (26) had been trying to have a second child for a while. This baby was finally born last year at a time when coronavirus numbers were escalating in Sri Lanka.

A few days after he was born, he stopped drinking milk and developed phlegm. A visit to a nearby doctor offered temporary reprieve but he then got worse and was taken to the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children. He passed away after being admitted to the ICU.

The baby’s parents tested negative for the coronavirus. But the baby tested positive so he was quickly cremated, despite the dazed parents’ plea for burial as cremation went against their religious beliefs – young parents who were still grappling with the loss of their new-born. A baby they had waited years for. For some reason, this cremation was also ghoulishly televised.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates points out that before we become bodies, and in order to exist in the world, there is love poured into all of us to live.

I imagine there was love poured into this 20-day old infant to prepare him for his life. There would have been arrangements made in anticipation of his birth – baby shirts sewn; eau de cologne, baby lotions, a cot and nappies procured; harried medical check-ups in the midst of a pandemic and curfews. We know his father was a three-wheeler driver and his livelihood may have been disrupted with the curfews. The baby was named Shaykh Fa – a hybrid of his parents’ names and his six-year-old sister, Shifka. More love.

When the news of the first forced cremation in Sri Lanka broke last year, cremation was held up as the only viable option – there was uncertainty about whether COVID-19 infected dead were still infectious. Health experts looked to Ebola and previous virus strains for cues on how to proceed. It was a murky time. There were murmurs of grief but during a pandemic, public health and humanity take precedence.

When 20-day-old Shaykh was forcibly cremated by Sri Lankan authorities in December 2020, the world was a year into the pandemic. We had more information about the virus and adapted accordingly. The WHO’s advisory on facemasks had changed drastically – just ten months ago, they maintained masking was optional and for caregivers or the sick only. Vaccines are now being rolled out. We’ve come a long way since.

Our personal pandemic habits have changed. My parents have stopped money laundering – washing currency notes and hanging them out to dry. We don’t have the energy to sanitize groceries and we now know this isn’t necessary as the virus is largely airborne. Our grocery shopping is largely online. I avoid A/C environments and large groups, opting for outdoor, open-air spaces for any meetings. Pandemic fatigue has set in and there doesn’t seem to be a finish line in sight. I can't gauge what the future will look like even a week from today. But we are masking, washing our hands, social distancing, keeping faith and plodding on. What else can we do?

Methods of testing, treating and dealing with the dead have evolved. We are told the virus requires a living organism to transmit. In most countries, both cremation and burial are permitted. But the Sri Lankan state defiantly continues to burn its COVID-19 infected dead. Despite public outcry requesting burial as an option, despite WHO regulations to respect fundamental rights, despite scientific evidence, despite two committee reports stating that burials are permissible, despite religious leaders of all faiths voicing their dismay, despite international pressure, despite grieving families refusing to claim their dead loved ones and be complicit in this burning, despite, despite, despite.

The conversations around forced cremations in Sri Lanka continued for most of last year. It reached a zenith after Shaykh's death, prompting renewed protests. A photograph of Shaykh was circulated on social media, and I worry about consent and privacy with things like these, but seeing his photograph was a jolt.

‘Shaykh’ in Arabic means head, chieftain, teacher. We have become so inured to this country accumulating bodies. It took the death of a 20-day-old baby to remind us of the lives that precede these bodies and the lives that are left behind.

6/

Sometimes I go online to read the comments around forced cremations in Sri Lanka. Most take on familiar tropes: Muslim exceptionalism/This is a Sinhala Buddhist country, know your place/Whataboutism. Some are genuine incredulity.

“I don't understand it,” noted an exasperated commenter on an Instagram post. “When you’re dead, you're dead. What does it matter what happens with the body?"

And he's absolutely right. Muslims believe that religious rites should not harm anyone else. Practices evolve with contemporary circumstances. If there was scientific evidence there was transmission through burials this conversation would not be happening.

Muslim funerals are taken within 24 hours. There is no undue prolonging of anguish. To work through your grief and put together a funeral in a day is taxing. Funerals are also held at home instead of a funeral parlour and arrangements need to be made. But many people come together swiftly and without much fanfare— family, friends, community, mosques — to make this happen.

There is an intimacy and simplicity in the last rites which I appreciate. The body is washed by a few loved ones. It is draped in a plain white cloth. There is no casket, fine attire and no embalming process — which is why the funeral is taken so soon. The body is laid out on a barebones frame. There is a group prayer for the life that is departed – it is believed that life on earth is only a small blip in a larger existence. The body is then buried in a plot of land. You arrive in the world with nothing, you leave in the same way.

What is being asked is not the funeral rituals in its entirety. Only the burial.

As so many have noted: “When you’re dead, you're dead. What does it matter what happens with the body?" There is a lot of discussion about bodies and what should and shouldn't happen to these corpses. What is absent in this commentary are the people these bodies leave behind.

Death rituals offer comfort to the living. They help the living adjust to loss, to briefly honour a life. The death of a loved one can shatter parts of you, leaving you to pick up the pieces for years in ways you didn’t quite anticipate. Sometimes it could feel like a hairline fracture – you might not even realize there is a crack until you apply pressure and find yourself recoiling in pain.

Often our reaction to something reveals more about us than the situation itself and this is worth deconstructing. Perhaps we should flip some of these questions to those advocating forced cremations in Sri Lanka.

How did you feel when someone you loved died – did you do everything you can to ensure their last moments on earth honoured the life they lived? What does your inability to understand how a small gesture would bring so much comfort to so many mired in grief say about you? What is it about your fellow citizens requesting to bury their dead that disturbs you?

The Sri Lankan state’s response to a request for burials is the equivalent of someone looking into your eyes and deliberately pouring acid onto broken skin when you asked for a bandage. The one country/one law argument and the rickety bad faith science that bolstered the rationale for forced cremations has left the ashes of a few hundred forcibly charred bodies behind. During a slow-burn time, when people are still grappling with the effects of the pandemic, the state is zealously keen to harm when it has the power to heal.

The contortions around the issue have been fascinating. Authorities began freezing unclaimed bodies, promising to allocate a land for burial and then reneged on the promise. One medical expert said that the virus could live on in a dead body for 100 years, another said the bodies could be utilized as bio-weapons. At one point, the state decided it was a good idea to export the dead bodies and outsource burials to the Maldives – a bizarre, unwieldy solution which applies additional pressure to already-overworked frontline workers who are bearing the brunt of this pandemic and are working at great personal cost.

Someone in a meeting dusted the butter cake crumbs from their fingers, put down their teacup and said, “Well, if they don’t want to be burned here, they can be buried in the Maldives.” Others in the room nodded and agreed to this idea.

It was a real-life manifestation of the “Go back to Saudi Arabia/Pakistan if you don't like it here” comment that many Muslims receive on the internet.

"Emotion also has a place in public policy. We're humans, not robots,” writes Zadie Smith. What we are witnessing is the mechanisms of leaders who have forgotten this. It is also both a spill over and reinforcement of decades of institutionalized racism which transcends political lines. In Militarizing Sri Lanka, Neloufer de Mel examines how the erosion of democratic institutions and the freedoms and rights of people and an increase in violence within everyday social relations often corresponds with a reliance on militarization and military thought. These are also symptoms of growing militarization both as a process and ideology which persisted during the war and has lingered as post-war residue.

In a podcast, writer Eula Biss, draws on Susan Sontag's writing on AIDS and its metaphors and examines how disease as an enemy leads too easily to xenophobia and racism and how military metaphors start tinging reality. Sontag writes how war metaphors can shape and obscure lived realities: we have seen this in the war on drugs, war on terror and now, the war on the pandemic. “War-making is one of the few activities that people are not supposed to view “realistically”; that is, with an eye to expense and practical outcome. In all-out war, expenditure is all-out, unprudent – war being defined as an emergency in which no sacrifice is excessive,” she notes.

Sri Lanka is well past military metaphor. The state championed to victory on the urgency for security and discipline. It has approached the pandemic with the same strategy as it would a war. This is evident in its rhetoric, approach, messaging. In a war, you need to shed the soft parts which make you human and which strengthen the bond with the world around you. The ‘Other’ you visualize and fight requires a similar desensitization. Your task is on your goal and nothing else.

Love, compassion and kindness aren’t in war lexicons or thought. By extension, it is absent in the state’s pandemic response. What then, by this logic, are a few forcibly burnt bodies in-between?

7/

This is the part of the essay where I should offer you a grand truth. I was hoping that at the end of this endeavour, I will emerge with some inspiring words which will lead to radical softness. All I have is an exhaustion and heaviness and I feel it leaking into the words you are reading now. I thought this piece would be a few paragraphs but it has taken two months to write and has occupied so much of my headspace.

In Sri Lanka, we are exactly a year into the pandemic. Our numbers are at an all-time high, the death toll continues to steadily increase but it is also life as normal in so many ways because to admit to an escalation of the coronavirus would be to backpedal on a victory that has already been declared against the pandemic. There is little communication on caution and safety nor any emphasis on compassion. Larger public health is now down to individual actions.

I have also felt uncomfortable writing this. To hold up my faith – something deeply private to me – for scrutiny and to be critical in a climate which is not favourable to critics. This long, inelegant attempt to map an empathy flow chart amidst an extraordinary lack of compassion feels impractical against the weight of this country’s history: this is who I am, this is what I believe in, this is what my community is asking for, this is why we are asking for it, please sir, please sir will you grant us a basic human right.

In the middle of figuring how to live through a second year of a pandemic, I am added onto a WhatsApp group with updates on someone who is dying.

I have been on WhatsApp groups to plan bachelorettes, birthdays and baby showers. I have groups for news updates, food orders, varying friend circles. This is the first time I am on a WhatsApp group for someone I know, whose body is on that tenuous bridge between life and death. The group was partly for the convenience of mass updates. It soon became a way for us to digitally converge and grieve for a life that was, while being physically apart. The updates were in real-time and are clipped but packed with details: symptoms, doctor's notes, times, music being played to soften the pain. After the death, there is an outpouring of sadness.

While reading these elegies I catch glimpses of what it means to live a full life. We mourned someone who engaged with the world critically and with curiosity, a sharp political conscious and empathy. Who was quick to offer help and encouragement.

I don’t know if most of us are exceptional enough to effect large scale change, no? I mean I hope you can. I remain brutally realistic about the limits of my ability and sphere of influence. Perhaps all we can really hope for is to be outrageously empathetic and touch the lives of the people within our sphere and hope this is carried forward into a wider social equation. People never forget how you make them feel – whether good or bad. The pandemic has warped and contracted so much of our life that it’s been harder to remember this in the last year.

Speak to anyone about the pandemic long enough and gradually what they will talk of is loss amidst swirling uncertainty. Loss of life events, a loss of income, travel, families separated across borders, ruptures in normalcy, robust relationships disintegrating like butterfly wings in the rain. We lost so much in the last year. When we take stock of the pandemic later, some of these losses will be too quiet, shapeless and ambiguous to document and quantify.

To live as a Muslim in Sri Lanka in recent years is to exist in a state of disbelief and heartache. To die as a Muslim in Sri Lanka today is to die knowing that your country has so little regard for you. To die in a home where you are not seen as equal and where you are told in so many different ways that you don't belong. This is also a type of loss.

I have been preoccupied with the things that bring us together at a time like this and have sat at my desk wondering how to end this. The soundtrack accompanying me today is an invisible funeral procession I can hear in the distance from my window. The beats of the mala bere — a thammattamma and dawula covered in white cloth to muffle the volume — and mournful strains of the horaneva are a reminder of a body a few hundred metres away that will soon be laid to rest. Occasionally, the whooooosh of a fighter jet and the staccato of helicopters suddenly fill the sky – rehearsals for Independence Day.

One day during the curfew we were allowed to go to pharmacies to pick up essentials. It was a few hours of freedom after weeks indoors and I walked to a nearby pharmacy to pick up medication which wasn't available with pharmacy delivery services. The line outside the pharmacy was long and slow. We were an S-shaped curve in the hot April sun, spilling into the car park and winding out four doors past the pharmacy. We had come from different areas and were a group of people of all faiths, sizes and ages. The man in front of me had two pairs of surgical gloves on and a skin-sweat-sheen was visible through the latex. He had come from a few towns away because he was running out of medicine, he explained. This was the only pharmacy which stocked it. Many of us swapped stories about the lockdown as we stood there for over one and a half hours. A line-cutter discreetly tried to slip into the middle of the queue and was met with such unexpectedly vocal resistance from multiple people who had been standing in the sun for an hour that he was taken aback. He mumbled he didn't see where the line began and slunk off.

What I remember from this day was kindness. I saw an elderly, visibly Muslim woman offered a plastic chair to sit on. A gentleman ushered in a few others under the canopy of a nearby shop: "we're going to be here for a while. Might as well stay in the shade. We’ll keep each other’s places in the line, don’t worry". A woman in front of me asked if I would like to share her umbrella when she saw me squinting in the sun.

On some days you can see the softer contours of this country. I like to believe that these are the parts of Sri Lanka that will endure once we emerge from the other side of this pandemic. I need to believe this. I need to.

Update: On 25 February 2021, after 10 months of forced cremations, the government of Sri Lanka issued an updated gazette allowing burials of COVID-19-infected dead.

Till 1 October 2021, the only burial site in the country for COVID-19-infected dead was in Oddamavadi, forcing families and loved ones to travel across the country to bury their loved ones. A family in Colombo, for instance, is required to travel for 6 - 7 hours to bury their dead and forced to deal with military scrutiny and intimidation during the burial process.

This is such a heart-breaking write-up, Adilah. The pain is palpable; and one wonders if the young of this world deserve this pain; when all they should be doing is to have joy, fun and dreams filling their lives with.

It's such a difficult time, perhaps across the world. Especially for Muslims in light of the rampant islamophobia. I totally empathise with this; and I don't have words to express it deeply enough. All that I can say is that perhaps the world has always been this way; as an amateur student of history, I have noticed, not without surprise - that pain, oppression, exploitation, racism, genocides have been the constant throughout human history; while peace has been a blip of an aberration. Peace never lasts in an unending stream of conflict in human history. In my studies, I have noticed that there is NO justice served by the so-called God against oppression; that except for a few exceptions, the murderers and the mass killers always get away with it. That is the sad truth.

So, in midst of all this pain; it would only be apt, I reckon, to get on with living like an ostrich sometimes to keep sanity. Easier said than done; I am fighting the same battle..

There is a lot of kindness and a lot of us who arent racist! sadly the media fuels the racism by giving too much mileage to the minority who are racist! There is only one minority in Sri Lanka in my opinion and those are extremists who want to alienate other religions and ethnicities. They are not buddhists, they think they are but they are not! The rest of us apologize on their behalf!